The History of Curaçao

In many ways, Curaçao is the historical nexus of the Netherlands Antilles. The island, with its large and protected natural port, was charted before the 16th century and eventually became a major center for mercantile commerce. It is the birthplace of Papiamentu (as it is spelled on Curaçao), the polyglot lingua franca of the ABC Islands which is spoken to an extent as far north as the Netherlands Antilles islands of Sint Eustatius, Saba, and Sint Maarten. And the island is, on another level, the birthplace of the famous liqueur, Curaçao, perhaps more well known in some circles than the island itself.

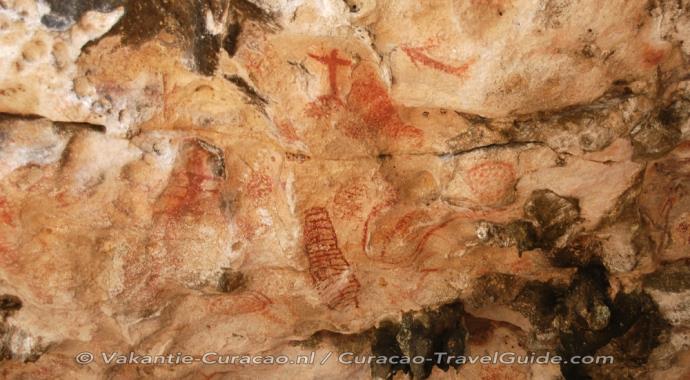

The history of Curaçao begins with Amerindian Arawaks. The Arawaks and their subgroups migrated from regions of South America some 6,000 years ago, settling on various islands the discovered as they embarked on a centuries-long northward trek. The group that ended up in Curaçao were the Caiquetios, who gave the island it's name.

After the late-15th-century voyages of Christopher Columbus put the Caribbean, literally, on the maps, the area was wide open for European exploration. The Spanish soldier and explorer Alonso de Ojeda, joined by the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, set out on a voyage (1499 - 1500) to chart much of the South American coast and, in turn, several offshore islands in the area. One was Curaçao. As an aside, disputed claims are par for the course when it comes to Vespucci. One of many stories has it that during his voyage with de Ojeda, a number of sailors on his ship came down with scurvy, whereupon he dropped off the hapless souls on Curaçao on his way to South America.

On his return, he found the sailors alive and happy-presumably cured by the abundance of Vitamin C-laden fruit on the island. He then is said to have named the island Curaçao, after an archaic Portuguese word for "cure". Of course, Vespucci was Italian, not Portuguese, and de Ojeda was Spanish, but these stories seem to take on a life of their own, and are often much more fun than the real story. A more convincing theory is that the Spaniards called the island Curazon, for "heart", and the mapmakers of the day converted the spelling to the Portuguese Curaçao.

At any rate, soon after de Ojeda's voyage, the Spanish came in larger numbers. By the early 16th century they had pretty well determined that the island had little gold and not enough of a fresh water supply to establish large farms, and they abandoned it. Finally, the Dutch West India Company, a quasi-private, government-backed company, laid claim in 1634. The company installed the Dutch explorer Peter Stuyvesant as governor in 1642, and he soon established plantations on the island, each with its famous landhuizen-structures that can still be seen today. The plantations foundered in various forms of agriculture, but some were successful in growing peanuts, maize, and fruits. They soon found their niche in the production of salt, dried from the island's saline ponds. Within a few years after establishing the farming industry and some form of rule on Curaçao, Stuyvesant moved on to bigger shores.

With its deep port and protected shores, and with the establishment of several large forts, Curaçao soon became a safe place for the Dutch West India Company to conduct commerce. Chief among its endeavors was the trade of slaves from Africa, who then went on to the other islands of the Dutch West Indies and to the Spanish Main. It was during the slave trade days that the language Papiamentu began to form. The language, a mixture of Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and African dialects, became the main form of communication between slaves and their captors.

Also during this time, Jewish families from Amsterdam established settlements on Curaçao and attracted others from Europe and South America, fleeing from the remnants of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions. By the early 18th century, the Jewish population in Curaçao had reached 2,000. In 1732, the community established the Mikve Israel Emanuel Synagogue in Willemstad, a structure that stands today. It is one of the oldest synagogues in the Western Hemisphere still in use.

During the early 18th century, the island's deep port and strategic position attracted the British and French, who as always were busy in the Caribbean, fighting over various islands in desperate struggles to control the profitable trade routes and sugar plantations of the larger islands. Brittain tossed out the Dutch twice, from 1800 to 1803, and again from 1807 to 1815. The 1815 Treaty of Paris settled a lot of disputes in the Caribbean, and it gave Curaçao back to the Dutch West India Company. Soon after the Dutch retook the island, it languished for a century. Slavery disappeared, and social and economic conditions were harsh.

In 1920, oil was discovered off the Venezuelan coast. This signaled a new era for Curaçao, and for its sister island in the ABCs, Aruba. The two islands became centers for distilling crude oil imported from Venezuela, and Curaçao's Royal Dutch Shell Refinery became the island's biggest business and employer. Immigrants headed for Curaçao, many from other Caribbean nations, South America, and as far away as Asia. During WW II, the Allies judged Curaçao and its refinery to be important enough, and strategic enough, to establish an American military base at Waterfort Arches, near Willemstad.

After WW II, Curaçao joined the rest of the Caribbean in a loud clamor for independence. What it got instead was a measure of autonomy as an entity within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Curaçao, along with, Bonaire, Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten, became the Netherlands Antilles, with the administrative center in Willemstad. Aruba separated from the other five islands on January 1, 1986. Sint Maarten and Curacao became independed on October 10, 2010 and the islands of Bonaire, Saba and Sint Eustatius became special municipalities within the country of the Netherlands.